Cincinnati Police Lieutenant John Poppe

Cincinnati Police Lieutenant John Poppe

-by Lieutenant Alan March, Cincinnati Police Department, retired

Greater Cincinnati Police Museum History Committee

John Poppe ran away from his Cincinnati home as a teenager. In his twenties, he enlisted in the US Army and became a cavalry trooper. Fighting Ute Indians at the Battle of Milk Creek, Poppe’s heroism was recognized with the Medal of Honor. Back home in Cincinnati, Poppe became a police officer and continued to lead a heroic life.

John Poppe was born in Cincinnati in 1856. At the age of 15, Poppe left his home to work on a Kentucky farm. While working the farm, Poppe fell in love with the farmer’s daughter. Unfortunately, the farmer wanted his daughter to marry an older man, as old as the farmer himself. Despite the father’s misgivings, Poppe asked the girl to run away with him so they could get married. She turned him down. Crushed by the rejection, John Poppe disappeared from the farm. He headed West, alone, no longer caring what happened to him.

Poppe found work as a telegraph lineman. Strong, agile, young men were hired to climb the poles to maintain telegraph wires. Later, John Poppe worked as a blacksmith, becoming familiar with horses. This may have encouraged him to enlist in the US Army and seek assignment to the cavalry. Poppe was assigned to the 5th US Cavalry in company F. He was made sergeant by the time he was twenty-three and was stationed in Wyoming. In neighboring Colorado, the Ute Indians were objecting to staying on the reservations. An expedition of cavalry, infantry, and civilian teamsters driving wagons was formed under the command of Major Thomas Thornburg and sent out to pacify the Utes. Young Sergeant John Poppe was a member of the Thornburgh Expedition, which stumbled into what became known as the Battle of Milk Creek Colorado.

The Battle of Milk Creek raged for six days and is said to be the longest sustained fight between US and Indian forces. Major Thornburgh was killed on the first day. Junior officers and non-commissioned officers were left to lead their men.

The scalping and mutilation of Custer’s troopers at the Little Big Horn just three years earlier must have been in the minds of Thornburg’s men. While the men of the 5th Cavalry accepted that death may come with the job, none of them wanted their bodies desecrated. They were going to fight to live.

The scalping and mutilation of Custer’s troopers at the Little Big Horn just three years earlier must have been in the minds of Thornburg’s men. While the men of the 5th Cavalry accepted that death may come with the job, none of them wanted their bodies desecrated. They were going to fight to live.

Minutes into the battle on the first day a detachment of twenty-one men was separated from the relative safety of the circled wagons. Sergeant John Poppe led ten troopers out of the improvised defensive works to link up with them. Poppe’s squad fought their way more than a quarter mile to link up with the detachment. The combined detachment battled its way back to their lines and inside the breastworks comprised of overturned wagons, dying horses, and crates of supplies. Though nearly every man of the detachment was wounded, no one was left behind.

As the siege developed, the Utes set fires to the brush near the encircled wagons. A captain ordered Sergeant Poppe to take some men outside the defensive ring to set counter fires, to deny the Utes cover. Without assembling a squad, Sergeant Poppe leapt outside the breastworks on his own. Isolated, away from his comrades, vulnerable to fire from the Indians, Poppe set several fires well beyond the troopers. He returned safely to see that his fires had burned all the cover to the northeast of the troopers’ position, denying the enemy close concealment. The fighting slackened appreciably after that. Several couriers were sent out in different directions to seek help for the besieged troopers.

A relief column of 350 men from Wyoming arrived on the sixth day and drove off the Indians. However, the troopers and teamsters of Thornburgh’s column had lost thirteen killed and forty-two wounded in the battle.

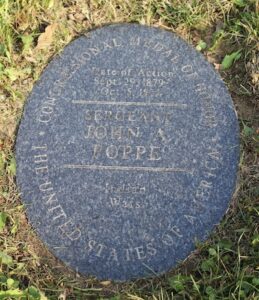

In 1880, Sergeant John Poppe received the Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest military medal for bravery. The citation for his medal reads simply, “For gallantry in action.” Photos of that medal are on display in the Greater Cincinnati Police Museum.

John Poppe served in the army for a few more years, then returned home to Cincinnati. Looking for work in 1888, he applied for the job of policeman. The Cincinnati Enquirer described how Poppe silently handed the police examiner a piece of paper and a small cloth covered box with a hinged lid. The paper was Poppe’s discharge from the US Army. On the back of the document was a simple notation indicating he had won a medal for bravery fighting Indians in 1879. The examiner opened the small box and saw Poppe’s Medal of Honor. Poppe was hired.

John Poppe served in the army for a few more years, then returned home to Cincinnati. Looking for work in 1888, he applied for the job of policeman. The Cincinnati Enquirer described how Poppe silently handed the police examiner a piece of paper and a small cloth covered box with a hinged lid. The paper was Poppe’s discharge from the US Army. On the back of the document was a simple notation indicating he had won a medal for bravery fighting Indians in 1879. The examiner opened the small box and saw Poppe’s Medal of Honor. Poppe was hired.

John Poppe started as a substitute patrolman, the entry-level position for the job. Within one month, Poppe was elevated to the rank of full patrolman.

By 1890 Poppe was appointed to the rank of sergeant and assigned to the 9th District, on Cincinnati’s west side. That station house stood at the corner of State Avenue and Dutton St. in the neighborhood now known as Lower Price Hill.

Just two years later, Poppe was promoted to lieutenant. John Poppe was recognized as a man of skill and ability.

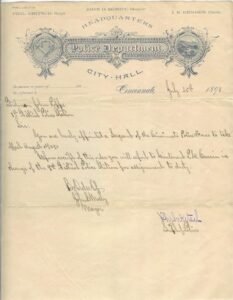

In 1894, Lieutenant John Poppe was given the prestigious position of Night Chief. Essentially, the Night Chief acted as the chief of police during the night hours. All shifts from the districts were required to report to the Night Chief any unusual or interesting occurrences which occurred during the nighttime hours. The Night Chief would sit in his City Hall office, waiting for the calls about murders, stabbings, robberies, or fires. However, District lieutenants and sergeants preferred to tend to their own work and notify the chief’s office in the morning. Feeling he was out of the action, Night Chief Lieutenant Poppe went out onto the streets to patrol on his own. He was an active Night Chief.

Some of his Poppe’s actions were as common as taking a drunk off of the streets. In July of 1894 Poppe left his office in City Hall and walked south along Central Avenue. At George Street he encountered John Manuel, who was clearly intoxicated. Poppe told Manuel he was under arrest. Rather than submitting, Manuel pulled out a knife and stabbed Poppe in the right arm and right breast. Wielding his fists and baton, Poppe succeeded in knocking him down and arresting his assailant. Manuel was charged with “Cutting to Kill.” He served six months in jail and had to pay a $200 fine.

Lieutenant John Poppe regularly displayed courage in the face of danger. In January of 1897, Charles Pelton of the Ohio Anti-Saloon League commended Poppe for arresting a stabbing suspect when Poppe, “plunged into that dark den of horrors” to arrest a man who had stabbed someone in a nearby saloon. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that Poppe had, “succeeded in capturing a knife-user out of the midst of a tough gang.”

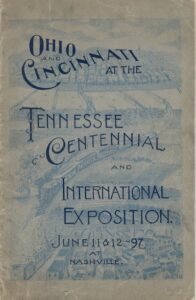

In the summer of 1897 Poppe was given command of one a company of Cincinnati Policemen at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition being held in Nashville throughout much of the year. The Cincinnati retinue totaled more than 100 men, including Colonel Deitsch, his staff, and the two companies of patrolmen. The patrolmen were selected based upon physical fitness and their stature: not one selected was under 5’11” tall. All the men were provided brand new uniforms for the event. June 11 was Ohio Day and June 12 was Cincinnati Day at the expo. President McKinley, attending the expo on both days, personally requested that Colonel Deitsch and the Cincinnati Police be his escorts. The “Blue Coats” of the Cincinnati Police Department were the lead elements in a parade which crossed the exposition grounds. Several times a day, they demonstrated their military precision in drill on the fair grounds and paraded through the streets of Nashville.

In 1902, when President Theodore Roosevelt took a train west to hunt bear in Missouri, his itinerary included a brief stop in Cincinnati. Though the stop was to be less than half an hour, Superintendent of Cincinnati Police Phillip Deitsch, dispatched a company of policemen to welcome the president. Leading the company was Lieutenant John Poppe. Colonel Deitsch, Lt Poppe and 40 patrolmen wore their parade uniforms complete with dress coats, dress batons, red tassels dangling from their batons, aluminum sockets in which the batons were to be carried on the belt, and buff-colored leather gloves as they welcomed the president at the Little Miami Depot at the eastern edge of Cincinnati. On November 12, 1902, Colonel Deitsch, Lieutenant Poppe, and about forty Cincinnati patrolmen greeted the president. Having been a police commissioner himself in New York, President Roosevelt was naturally very interested in the company of men standing at attention before him. The president spoke briefly from the platform of his train car, then quickly stepped off the train. He walked up to Colonel Deitsch and grasped his hand in greeting, saying “I am happy to meet you again.” Colonel Deitsch called Lieutenant Poppe forward and introduced him to Mr. Roosevelt. The colonel explained that Lieutenant Poppe had served in the army and won the Medal of Honor. The old Indian fighter told the story of Milk Creek. The president, himself an accomplished historian, indicated knowledge of the battle. The two former soldiers warmly shook hands, having shared the common experience of combat. The president said, “I’m more than pleased to meet you.”

In 1902, when President Theodore Roosevelt took a train west to hunt bear in Missouri, his itinerary included a brief stop in Cincinnati. Though the stop was to be less than half an hour, Superintendent of Cincinnati Police Phillip Deitsch, dispatched a company of policemen to welcome the president. Leading the company was Lieutenant John Poppe. Colonel Deitsch, Lt Poppe and 40 patrolmen wore their parade uniforms complete with dress coats, dress batons, red tassels dangling from their batons, aluminum sockets in which the batons were to be carried on the belt, and buff-colored leather gloves as they welcomed the president at the Little Miami Depot at the eastern edge of Cincinnati. On November 12, 1902, Colonel Deitsch, Lieutenant Poppe, and about forty Cincinnati patrolmen greeted the president. Having been a police commissioner himself in New York, President Roosevelt was naturally very interested in the company of men standing at attention before him. The president spoke briefly from the platform of his train car, then quickly stepped off the train. He walked up to Colonel Deitsch and grasped his hand in greeting, saying “I am happy to meet you again.” Colonel Deitsch called Lieutenant Poppe forward and introduced him to Mr. Roosevelt. The colonel explained that Lieutenant Poppe had served in the army and won the Medal of Honor. The old Indian fighter told the story of Milk Creek. The president, himself an accomplished historian, indicated knowledge of the battle. The two former soldiers warmly shook hands, having shared the common experience of combat. The president said, “I’m more than pleased to meet you.”

By 1904, Lieutenant John Poppe was made the assistant to the Inspector of Detectives.(2, 7). Essentially, this made Poppe the chief of detectives in Cincinnati. His pay was $1,700.00 per year. A year later, Poppe and Detective McDermott were detailed to the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt. In our nation’s capital, Poppe and McDermott were assigned to locate and observe known criminals from Cincinnati and to stop them from committing crimes during the inaugural festivities.

In 1906, the CPD undertook the extraordinary measure of installing a telephone in Lieutenant Poppe’s home. This direct line from police headquarters gave the department instant access to one of its most dependable officers.

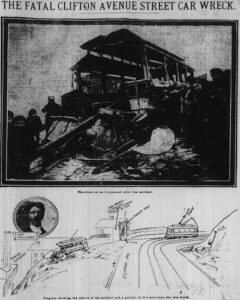

Living in College Hill, a north suburb of Cincinnati, Poppe used the streetcar to get to work downtown. On January 30, 1909, Poppe’s streetcar was traveling south on Clifton Avenue, down the hill toward Vine St. He noticed it was accelerating at an alarming rate.

The motorman operating the car had lost control, vainly pulling on the brake. As the trolley sped toward the sharp curve just above Vine St. Poppe joined the motorman, and together they tried to stop the car. Shouts from pedestrians on the sidewalk witnessing the terrifying event encouraged the passengers to leap off to safety, but none did. The streetcar jumped a curb and hit an iron pole just feet away from a high embankment and 150-foot plunge to houses below.

The motorman died of injuries he sustained. Lieutenant Poppe suffered devastating injuries: his chest was crushed as was his left leg. His ribs were broken and lung damaged. The next day, Poppe’s leg was amputated above the knee. Though twenty passengers were injured, the only fatality was the motorman. Poppe’s quick action was credited with saving lives.

Well wishers from across the country sent letters and telegrams to Poppe as he convalesced in Cincinnati’s City Hospital. Notables such as Congressman Nicholas Longworth (son-in-law of Theodore Roosevelt) and former mayor of Cincinnati Julius Fleischman wrote to Poppe praising his bravery and wishing  him a full and speedy recovery. Cincinnati’s City Council passed an ordinance allowing Poppe to remain on the force, at full pay, despite being an amputee. Council commended Poppe citing his, “…act of unselfish bravery and heroism.”

him a full and speedy recovery. Cincinnati’s City Council passed an ordinance allowing Poppe to remain on the force, at full pay, despite being an amputee. Council commended Poppe citing his, “…act of unselfish bravery and heroism.”

John Poppe continued to serve the Cincinnati Police Department until retiring March 1, 1913. Among the accolades Poppe received upon his retirement, was a hand lettered testimonial scroll, which bears his photograph. The testimonial reads,

“From the Cincinnati Police Department to Lieut John Poppe, Lieut of Detectives, from the members of Police Traffic No. 1, who take this means of expressing the High Regard and Esteem in which he is held by them, and at the same time, their best wishes for his future success and happiness.”

Below that is a list the names of 61 men of the Cincinnati Police Department who preserved for posterity their sentiments. The document is dated Feb 28, 1913. The next day, Lieutenant John Poppe retired from the Cincinnati Police Department. The scroll is now in the collections of the Greater Cincinnati Police Museum.

John Poppe remained in Cincinnati, living at the Westwood home of his daughter, Elizabeth Poppe Guckenberger. Poppe died surrounded by family on January 16, 1926, at the age of 69.

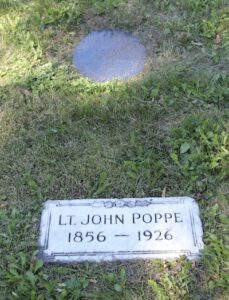

Lieutenant John Poppe is buried in Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery, section 62, lot A37, next to his wife Charlotte. A simple white headstone identifies him as “Lt. John Poppe.” It is a rarity that a police officer’s rank is mentioned on a gravestone. Above that is another stone. That one is oval, polished black. It reads: