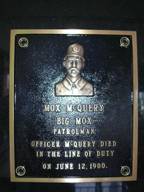

Patrolman William Thomas “Big Mox” McQuery | Covington Police Department

Badge: 7

Age: Almost 29

Served: 4 years

June 1896 to June 12, 1900

OFFICER

William, known as Mox, Big Mox, and Moxie, was born on June 28, 1861 in Garrard County, Kentucky to Alexander M. and Margaret Jane (Naylor) McQuery. By 1870, Alexander moved his family, including Mox’s older sisters, Elizabeth Angelene “Angie” and Mary Jane “Jennie”, to Covington where he worked as a plasterer. We believe Mox worked for a time in his father’s trade, probably starting at about age 16.

BASEBALL

Mox also played amateur baseball with the Covington Kentons and was scouted in 1882. In 1883, he signed on with the Terre Haute Northwestern League. In 1884, he debuted for the Cincinnati Outlaw Reds of the Union Association. In 1885, Mox opened the season with the Western League Club in Indianapolis and moved to Detroit when the Detroit Wolverines purchased the club. On September 28th, he became only the second Wolverine ever to hit for the cycle.

While in Indianapolis, he met Isabelle (Buchanan) Shroyer, a divorcee who was abandoned by her husband before their son was five years old. He married Isabelle in Versailles and took in her 11-year-old son, William Andrew Shroyer.

Mox became one of the best-known men in America, having travelled from Maine to California playing baseball. When the National League was formed, he was always in demand and was ranked the highest among all league first basemen.

In 1886, he was playing for the Kansas City Cowboys of the National League where he was described by Kansas City newspapers as a great fielder and a very heavy hitter. The next year Mox was playing for the Ontario Hamiltons and later that year signed on with the Syracuse Stars. For the first time in his career, he settled in for multiple seasons. In 1888 he led the team to the International League Pennant. By the end of 1890, his .308 batting average was second on the team and tenth in the league. In 1891, Mox signed with the Washington Statesmen of the American Association and was still one of the league’s leading hitters. But he was slowing down.

In 1886, he was playing for the Kansas City Cowboys of the National League where he was described by Kansas City newspapers as a great fielder and a very heavy hitter. The next year Mox was playing for the Ontario Hamiltons and later that year signed on with the Syracuse Stars. For the first time in his career, he settled in for multiple seasons. In 1888 he led the team to the International League Pennant. By the end of 1890, his .308 batting average was second on the team and tenth in the league. In 1891, Mox signed with the Washington Statesmen of the American Association and was still one of the league’s leading hitters. But he was slowing down.

Early in the season, he signed with the Buffalo Trojans to play and officiate as Captain. By 1892, he was considered an old-timer and while courting Toronto he was hired by Evansville, Indiana. His career ended there with a total of 417 games played, 429 hits, 13 home runs, 160 RBIs, 231 runs scored, and a lifetime batting average of .271. Almost a hundred years later, Pete Rose had a fraction more hits per game played. Newspapers around the country were still writing about his baseball prowess almost 50 years later.

Baseball was not a full-time job in the 19th Century and between seasons Mox would work as a huckster out of Covington where he, Isabelle, and William made their home. By 1894, tired of the grueling work involved as a huckster, Mox tried to get jobs with baseball clubs but ended up going back to work as a plasterer until 1895.

POLICE DEPARTMENT

In June 1896, Covington Chief of Police Joseph W. Pugh recommended Big Mox be appointed to the Police Department as a Patrolman. Mayor Rhinock agreed. He was first assigned to bicycle patrol and performed excellent work. Chief Pugh described him as “one of the most faithful and loyal officers on the force,” and “quiet, unassuming, temperate, and methodical in all his habits.” He was often selected when a man possessing these qualities was necessary to do special work. In 1900, Patrolman McQuery was assigned to the poolroom district at 2nd Street and Court Avenue. He was considered the most popular man on the Department, possessed of more than ordinary intelligence, and “brave as a lion.” He, Isabelle, and his widowed mother, Margaret, were living at 171 Riddle Street. Isabelle’s son, William, had married and was living in San Francisco.

MURDERERS

Wallace Bishop

Bishop was born about 1876, the oldest of four children born to Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Bishop of Charleston, Illinois. They were known as a good, upstanding family. Mr. Biship moved his family to East St. Louis, Missouri where he worked as a printer. Wallace Bishop had an athletic build and better than average intelligence and reportedly had never been in trouble. But, about 1895, 18- or 19-year-old Wallace left his family, and they never saw him again, except behind bars.

The only report we can find after he left home was that in 1900, he was arrested for carrying a gun, convicted, sentenced to ten days at the Bellview, Missouri Jail, and apparently out on bond. He failed to show at the jail on the appointed date, May 10th.

Thomas Mulligan

Mulligan was born about 1878, the second son born to an alcoholic father in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Due to his drinking, his father had been institutionalized at least three times in the Danvers (Essex County) Asylum for the Insane, the first time of which was when Thomas was 18 months old. Thomas was 14 when his father died. On August 10, 1898, Mulligan was arrested for assaulting picnickers at the annual Lowell Picnic in Massachusetts. Until the spring of 1899, Thomas had been employed as a dyer in a cotton mill, and then he disappeared from his family.

The only report we can find after he left home was that in 1900, is that he was indicted for the theft of a diamond ring in Chicago but by June he had not been found nor arrested on the indictment.

We suspect that Mulligan and Bishop met up somewhere, probably around Illinois and were working as “yeggmen,” traveling from place to place with hobos while committing safecracking and other crimes. This class of criminals was one of the boldest and most treacherous criminals of the day. They were exceedingly difficult to track with law enforcement records as they were at the time and equally difficult to research now, more than a century later. Regardless of when and how they met, they formed a fast relationship that lasted until Bishop’s death.

INCIDENT

On June 8, 1900, a few minutes before 5 p.m., Bishop and Mulligan, fairly well dressed, got off a Lagoon streetcar in Ludlow and entered the The Jungle, an area near the entertainment spot call The Lagoon where hobos and tramps tended to congregate during the summer and drink. The dozen or more occupants of The Jungle that day were at ease with the arrival of the two men. The men approached one of the occupants and offered him two dollars saying, “Go get a keg of beer.” The tramp answered, “Two dollars ain’t enough.” The man replied, “The hell it ain’t.” The tramp defended the assertion saying, “No. Cap tried to get one for that the other day.” The man asked, “Who the hell is Cap?”

The commonly agreed leader of the tramps, known only as “Cap” was nursing a broken ankle and asleep. Having heard his nickname, he roused and lifted his cap off his face to see what the conversation was about. Either Bishop or Mulligan cried out, “that’s the son of a bitch, now! Kill him!” With that, both men pulled their revolvers, and shot him multiple times. One pulled a knife and stabbed the man. Cap was still breathing, so one of the men picked up a coupling pin and brought it down on his head, killing him. Everyone fled, including Bishop and Mulligan.

All of this was observed by The Lagoon’s caretaker, William Burke, from a roof garden where he was seated. He rallied The Lagoon’s forces, including Deputy Sheriffs Droege, Rich, and Geisen. They took up Winchesters (possibly Model 1897 shotguns) and started chasing the tramps. Five were captured and placed under arrest.

Mulligan and Biship boarded a horse-drawn streetcar.

Burke called Covington Police Chief Pugh and advised him of the murder and that the murderers were aboard a Lagoon streetcar. Chief Pugh contacted Sergeant Sanford who detailed Patrolman McQuery to the south end of the Suspension Bridge to intercept the streetcar. He was reinforced by Lieutenant B. Schweinfuss and Sergeant Sanford.

About 5 p.m., Patrolman McQuery stopped the car and jumped aboard. He found the men and ordered them off the car. No sooner than their feet touched the ground, Mulligan and Bishop pulled their revolvers. Patrolman McQuery then pulled his. A shootout ensued. Mulligan knocked Patrolman McQuery’s gun aside and it discharged into Bishop’s leg. Bishop shot Patrolman McQuery in the chest and as he went down grabbed his revolver. A bystander, Thomas J. McHugh, was also wounded in the thigh. Bishop and Mulligan then took off north across the Suspension Bridge.

About 5 p.m., Patrolman McQuery stopped the car and jumped aboard. He found the men and ordered them off the car. No sooner than their feet touched the ground, Mulligan and Bishop pulled their revolvers. Patrolman McQuery then pulled his. A shootout ensued. Mulligan knocked Patrolman McQuery’s gun aside and it discharged into Bishop’s leg. Bishop shot Patrolman McQuery in the chest and as he went down grabbed his revolver. A bystander, Thomas J. McHugh, was also wounded in the thigh. Bishop and Mulligan then took off north across the Suspension Bridge.

The bridge was crowded with people traveling in both directions after leaving their jobs for the day. Several Covington patrolmen took the streetcar across the bridge, got off on the Cincinnati side and began coming back south while others were pressing north in search of the murderers.

Bishop tried to hide behind a post waiting for the northbound officers in order to take them out. Mulligan tried to blend in with the panicked crowd of workers returning home across the bridge.

Bishop and Sergeant Sanford traded shots while poking out from behind two poles. Finally, Bishop ran further north and saw the officers coming south. He jumped some 92 feet into the Ohio River below, holding two revolvers high in the air.

Lieutenant Schweinfuss and Captain Feeney ran down to a coal barge to which Bishop was swimming. Bishop came aboard with a pistol in hand, aimed at Feeney, and pulled the trigger four times. The firearm, which turned out to be Patrolman McQuery’s, failed to fire and Schweinfuss placed him under arrest. The officers walked him toward police headquarters, followed by a crowd intent on lynching him. Bishop only smiled.

Captain Feeney then found Mulligan lounging around the bridge as if he were just one of the crowd. He gave up without resistance.

Patrolman McQuery was carried to Chief Pugh’s office and doctors were summoned. Drs. Singleton, Reynolds, Tarvin, Malloy, and Eckman responded. They deemed the bullet was in his lung and decided to have him transported to Cincinnati Hospital. Newspapers reported that there was little doubt that he would recover.

Dr. Reynolds removed Bishop’s bullet. Thomas McHugh was transported to St. Elizabeth Hospital with a leg wound. The murdered hobo leader, Cap, was transported to Menninger’s Morgue.

DEATH

When the patrol wagon arrived at General Hospital, Patrolman McQuery was immediately transported to the amphitheater for surgery. The surgeons found his intestines had been perforated five times. The bullet was found in his abdominal cavity. His prognosis was dire.

He lingered between life and death for four days. Only his grief-stricken wife was admitted to his room. Other than a brief bout of nausea and expected elevation of temperature requiring medication, he had a fairly comfortable day on June 10th. On June 12th,The Enquirer, an early morning newspaper, reported that he had improved substantially, giving doctors a glimmer of hope for his recovery, and attributing it to his powerful physique. But an afternoon newspaper, the Dayton Daily News reported his death. Until 10 a.m. in the morning he was progressing nicely, but shortly after he declined quickly and his wife was brought to his deathbed. And then he died, two weeks short of his 39th birthday, becoming only the second Covington law enforcement officer to die in the line of duty and the first of the Covington Police Department.

Isabelle (Buchanon) McQuery (45) lost her second husband, one by abandonment after less than four years and one by death after 14 years. Widow Margaret Jane (Naylor) McQuery (58) lost her only son. William Andrew Shroyer lost the only father he ever knew. The fledgling professional baseball world lost one of its biggest stars. Patrolman McQuery was also survived by his sisters, Elizabeth Angeline “Angie” (Robert) Tattershall McQuery and Mary Jane (Benjamin Franklin) Newkirk, and their children.

All day on January 13, 1900, thousands of men and women filed through the McQuery home to view the remains and offer their respects to the family. On January 15, 1900 at 1 p.m., every Covington officer met at 1 p.m. at the Police Building from which they paraded to Patrolman McQuery’s home. At 2 p.m., a funeral ceremony was held at the home with First Baptist Church Reverend C. J. Jones officiating.

After the service, the cortege formed up, led by a band and followed by the Police and Fire Commissioners, Board of Alderman, City Councilmen, county and state officials, Police and Fire Departments with their equipment, hearses, and carriages. The pallbearers were Covington Patrolmen Hughes, Schmeing, Keefe, and Farandorf. Honorary pallbearers were former Mayor Joseph L. Rhinock, Chief of Police Pugh, Mayor W. A. Johnson, and Police Commissioner Ed Pleck.

The cortege proceeded to Pike Street, then to Madison Avenue, to 15th Street, to Holman Street, to the Linden Grove Cemetery. Almost every Covington business was shut down as mourners lined the route. An estimated 5,000 people attended the graveside services.

INVESTIGATION

A few days before, a safe was cracked in Paris, Kentucky and the yeggmen were thought to have traveled north. Covington Detectives Crawford and McDermott looked at Bishop and Mulligan and determined that they fit the description. But they were never charged with the crime.

Wallace Bishop claimed that his name was William Burns, a mailing clerk from St. Louis, Missouri. He claimed to not know the name of Thomas Mulligan and that he met him at a small station about 55 miles northwest of Cincinnati on the Baltimore and Ohio Southwest railroad. Both, he said, arrived in Cincinnati about June 1, 1900 and on June 8th they decided to go south and ended up in Ludlow where they intended to board a train on the Southern Railway. They wandered into a tramps’ camp and, seeing a lot of empty kegs lying around, offered $2 for a keg. Just then, a man lying on the ground jumped up with two revolvers and asserted that no beer was wanted. Burns took one revolver from him and shot him with it. He had no knowledge of anyone stabbing the man.

When questioned why he shot the officer, Bishop claimed that he was excited and that Mulligan did not do any shooting. He then asked the reporter if the officer was hurt badly. When told that he may die, he asserted that it would go pretty hard for him then and, “I regret from the bottom of my heart that I did it.” Bishop had a tattoo of “W.B.” on his arm, seemingly supporting his nom de plume”

Mulligan gave the name of Thomas Lyons, alias Thomas Reynolds, and said that he was a peddler from Buffalo, New York. Otherwise, he said nothing for days regarding the incidents and his real identity.

Police, however, doubted their given names and origins and considered that they might be a couple of wandering safecrackers known as “yeggmen.” The working theory was that they had searched for, found, and killed Cap because he was an informant.

On June 9, 1900, having seen his picture in the Cincinnati Enquirer, Mrs. A. W. Winans of 707 W. 9th Street, identified him to Covington Police as Wallace Bishop, of a family with which she was well acquainted. The Winans and Bishops were neighbors in Charleston, Illinois before the Bishops moved to St. Louis. Mrs. Winans immediately wrote a letter to her old friend, Mrs. Bishop, advising her of the trouble her son was in.

Also on the 9th, Coroner Tarvin conducted an autopsy of the deceased tramp known only as “Cap.” He found five bullet wounds, extracted three .38 caliber bullets, and noted a five-inch stab wound to the chest. He scheduled a Coroner’s Inquest for June 11, 1900. Thousands came to view the body for purposes of possible identification, or morbid curiosity. There were several conjectures based on various levels of evidence, but none proved positive.

With a herculean effort, the story of Patrolman McQuery’s death was kept secret from the public long enough for Chief Pugh to gather the prisoners and escort them to Louisville aboard the Louisville and Nashville 2:30 train. As word of his death leaked out, mobs began to assemble, but quickly dissipated by 3 p.m. when they found they were already enroute.

Hamilton County Coroner Schwab, immediately upon notification of Patrolman McQuery’s death, responded to view the remains and ordered a post-mortem. He also scheduled an inquest on June 13th, as required by Ohio statute, allowing for the possibility that only Ohio residents could be compelled to testify. All witnesses requested, almost all from Kentucky, voluntarily attended and testified. Coroner Schwab rendered a verdict that Patrolman McQuery died from peritonitis caused by a gunshot wound caused by Bishop.

Covington Coroner Tarvin also scheduled an inquest. On the 14th, he rendered a verdict that Patrolman McQuery came to his death by a gunshot fired by Bishop with Mulligan as an accessory.

Cap remained unidentified and was buried in a pauper’s grave at Potter’s Field. His identity went to the grave with Bishop and Mulligan.

When news and pictures of the murderers arrived in Lowell, Massachusetts, a resident and Mulligan’s uncle, Michael Mulligan, set out to Covington to identify “Lyons” as Thomas Mulligan of Lawrence, Massachusetts. Thomas Mulligan’s mother mortgaged her household belongings to produce sufficient cash for Michael Mulligan to travel to Covington.

JUSTICE

On June 9, 1900, Prosecuting Attorney Bert Simmons took both men before Judge M. T. Shine for arraignment on charges of Murder for the death of Cap and Carrying Concealed Weapons. Bishop was additionally charged with Shooting with Intent to Kill Patrolman McQuery. The five tramps were arraigned as accessories to the murder of Cap. Judge Shine ordered them all held over for the Grand Jury already in session.

There was a great sentiment for lynching, but City Jailer Joseph Wieghaus, County Jailer John Maurer, and all the of the turnkeys were confident they could rebuff any attempt with their six-pound canon that Wieghaus had used during the war and trained the others in its use.

On June 14th, the Kenton County Grand Jury reported indictments for Bishop and Mulligan (as Lyons) and added Mulligan as accessory to the murder of Patrolman McQuery.

Wallace Bishop

Charleston, Illinois Attorney Reardon offered to represent Bishop for gratis. He first visited his client on July 10, 1900, having just arrived from the National Democratic Convention in Kansas City. He would be assisted by his cousin, the Honorable Wesley Reardon of Butler County, Kentucky. Judge Tarvin set the trial for July 24, 1900.

After the jury was empaneled and the prosecution presented its case, Attorney Reardon at 10:00 a.m., requested a recess until 2 p.m. to consult with his client. Upon return, Bishop took the witness stand. He alleged that he had been drinking heavily for three years and that he already had ten or eleven drinks at the hobo camp. He alleged that the wound to his leg was received at the hobo camp and that he returned fire in self-defense. He claimed that he was so pained from the leg wound and drunk when Patrolman McQuery approached that a man was coming at him with a gun, so he fired at Patrolman McQuery in self-defense.

The case went to the jury at 8:45 p.m. on June 25, 1900. They were not fooled by Bishop’s perjury so immediately set out to determine what level of homicide should be found. The first vote of deliberations where seven for hanging and five for a life sentence. At 10:45 p.m., Judge Tarvin was notified that the jury had reached a verdict. At 11 p.m., the jury returned a verdict of Guilty with a sentence of Death. Bishop was stoic, told of his regret at killing the officer, and complained that he did not have a fair and impartial trial. At 10:00 a.m. on July 27th, immediately after Mulligan’s jury had gone into deliberations, Bishop was brought before Judge Tarvin. He asked if Bishop had anything to say before sentence was pronounced. He said, “I have nothing to say.” Judge Tarvin told him he would be hanged at the Kenton County Jail on August 30, 1900.

Attorney Wesley C. Reardin immediately filed motions of all sorts, but most importantly for a new trial. That motion was overruled, but a motion for a 60-day delay for an appeal was granted. Another stay was ordered by the Kenton County Circuit Court on September 20th, and an appeals hearing was set for October 4th. That court affirmed the execution, and the attorney appealed to the Court of Appeals. The Court of Appeals reported on October 27, 1900 that the appeal was denied and that Bishop’s execution would be carried out on a date determined by the Governor. However, the Court of Appeals being reconstituted after the 1900 elections, Attorney Rearden resubmitted the case and a new trial was granted.

Judge Tarvin set the new trial date for March 12, 1901. His attorneys filed several more motions, most of which were directed toward a change in venue. Finding the witnesses, most of which were tramps and held for the first trial in the Covington Jail, was also problematic. Finding unbiased jurors, after the sensational incidents and first findings of the first trials of both murderers was equally difficult. Finally, after going through 200 Kenton County residents, 12 less than desirable to the prosecution were empaneled on March 15th. The entire trial lasted the rest of the day, with closing arguments set for the next morning. On March 16, the case was handed over to the jury. The first vote was nine votes for 21 years, two for life imprisonment, and one for hanging. The final verdict was Guilty and Life Imprisonment. Very content with that verdict, there would be no more appeals. On March 21, 1901, saying goodbye to his mother, he said, “Don’t worry, mother; I’ll behave myself in prison, and I’ll be free someday.” He did not and he was not.

Thomas Mulligan

On July 26, 1900, Mulligan was defended by Attorney John Oneal, who immediately asked for a continuance, which was denied. Oneal spent much of the day filing delaying motions, attacking the indictments, and other legal maneuvers. It took only 63 minutes to seat a jury, after which the court adjourned for lunch until 2 p.m. Oneal’s eloquent opening argument lasted 1 hour and 40 minutes. Commonwealth Attorney Glenn’s went another 40 minutes. Witnesses testified that both men fired shots into Cap after lifting his cap to identify who he was. Mulligan testified in his own behalf alleging that he and Bishop had been drinking heavily for four days, that Cap pulled a gun on him and Bishop, and that he only returned fire in self-defense.

At 9:16 p.m., the case was handed over to the jury. Again, the guilt was never in question. Their first vote was to determine the penalty. The first vote was eight for hanging and four for a life sentence. At 10:30 p.m., Mulligan was all smiles as night fell, and the jury foreman announced that they had not yet come to a verdict. When the jury returned in the morning, they asked to review the coroner’s report with regard to whether all the bullets fired into Cap were fatal. Somehow, those favoring hanging were convinced that maybe all of the fatal shots came from Bishop’s gun. They then came back with a verdict of Guilty and a sentence of Life Imprisonment. Mulligan noted, “That’s an awful long time, but it’s better than death.” As it turned out, it was not very long at all.

On August 2, 1900, weeping bitterly, he wished his condemned friend farewell as he was taken to the Kentucky Penitentiary in Frankfort.

EPILOGUE

Isabelle (Buchanan)(Shroyer) McQuery

On June 29, 1900, a benefit concert was held for Mrs. McQuery at The Lagoon’s amphitheater. On the 30th, Covington Courthouse personnel competed against newspapermen in a match game at the Covington Ball Park as another benefit for her. On May 7, 1901, Mrs. McQuery petitioned the Police and Fire Commission for a pension, asserting that she had become ill and destitute. We do not know what became of that petition. She went to San Francisco to live with her son, apparently before 1902. She married again, this time to United States Army 1st Sergeant George J. Bauer, and at 69 she lost him, her third husband, on October 4, 1924. She died 21 years later in San Francisco on February 1, 1946 at the age of 90 and is buried in the National Cemetery in the Presidio with her third husband. She was survived by her son, William Andrew Shroyer, two granddaughters, and at least three great-grandchildren.

Wallace Bishop

As soon as Bishop arrived at prison, he and Mulligan refused to work. After much remedial punishment, they finally submitted to the Warden, but each had earned themselves a heavy ball and chain.

Seventeen months later, from someone outside the prison, Bishop secured a revolver. On August 20, 1902, at 6 a.m., Mulligan, Lafeyette Brooks, and Bishop, all three convicted murderers, disarmed two guards and took their guns and keys. They relieved themselves of their balls and chains. With three guns, they ran across the prison yard exchanging shots with other guards to the Reed Building. There they found unarmed Foreman Charles Willis and took him hostage. They were joined by convicted murderer Albert Ransom and moved to the second floor of the building.

At 9:00 a.m., Captain Eph Lillard, Jr., the warden’s son, spied Ransom through a window and, with a Mauser rifle, shot him in the shoulder. Bishop and the Warden, Colonel Eph Lillard, Sr., negotiated Ransom’s safe passage to the prison hospital where he was found in possession of a 12” dirk knife. We cannot find his history after being shot.

At 10 a.m., Bishop sent a note to Warden Lillard offering to surrender if the warden would personally come to the Reed Building entrance to take their guns. Warden Lillard correctly suspected this would be a suicidal venture. Later, Frank Brooks delivered a message from Bishop to the Warden asserting that they would send their guns out with Brooks if Warden Lillard came to take them into custody.

Still suspecting Bishop had no intention of coming out of this alive and not knowing how many guns the convicts had, several guards were posted overlooking the Reed Building with instructions to act if there was any indication that they were prepared to do the warden harm or take him hostage. As Warden Lillard approached and the prisoners emerged, Bishop dropped his hands as if to draw a weapon. Captain George Fry armed with a Winchester shotgun (probably a Model 1897) shot him in the chest with buckshot. “We got Bishop! He is dead,” a guard yelled.

Mulligan and Brooks sank to their knees and begged for their lives. They were taken up, heavily shackled, and removed from the scene. Mulligan was taken to the hospital with a shoulder wound incurred during their running gun battle across the prison yard.

Bishop was not dead. He was taken to the prison hospital where he immediately called for a Catholic priest and Baptism. If he could not cheat justice on earth, it is apparent that he thought he was going to cheat God’s justice and eternal life. But soon after his sins were wiped away, he began sinning anew with his discourse toward the doctors and guards. He died at 5:45 p.m.

Bishop’s mother was immediately notified in Hammond, Indiana, but made no effort to retrieve or even accept his remains. Nor did the medical college want his body because it was not the time of year for dissections. He was unceremoniously buried in the prison graveyard on August 22, 1902.

Lafayette Brooks

Brooks died in another escape attempt on July 11, 1903 when he fell 40 feet from a window.

Thomas Mulligan

Since his failed escape with Bishop and Brooks, Mulligan was a quiet, but sullen prisoner and carefully watched. But, on April 13, 1906, he still managed to escape the prison by crawling under the floor of a shoe shop where he was assigned to work. He was captured that night in the village of Bloomington, fifteen miles away. After his capture, he escaped again from the transporting officer, but because he was handcuffed, he was quickly recaptured.

We can find no source for it, but we are informed that he thereafter became a model prisoner and was inexplicably released March 18, 1908, having served less than eight years for the murder of Cap, accessory to Patrolman McQuery’s murder, an unsuccessful escape attempt, and a successful one. We have not found anything regarding the rest of his life.

Margaret Jane (Naylor) McQuery

Patrolman McQuery’s mother, Margaret, watched another child, Mary Jane (Benjamin Franklin) Newkirk, die in 1905. Margaret was injured in a fall in the latter part of 1909 and died in the home of her last remaining and twice widowed child, Angeline (McQuery)(Johnson)(Tattershell) Dendler, on January 17, 1910. She was buried in Linden Grove Cemetery. Angie died the next year.

If you know of information, artifacts, archives, or images of this officer or incident, please contact the Greater Cincinnati Police Museum at Memorial@Police-Museum.org.

© In anticipation of the 125th anniversary of Patrolman McQuery’s murder, this narrative was further researched and revised May 28, 2025 by Cincinnati Police Lieutenant Stephen R. Kramer (Retired), Greater Cincinnati Police Historical Society President/CEO. All rights are reserved to him and the Greater Cincinnati Police Museum.