Patrolman Frederick Karsch | Cincinnati Police Department

Age: 36

Served: 1 year

April 4 to November 4, 1880

OFFICER

Fred was born on July 31, 1844 in Prussia to Alfred (of Russia) and Isabella (of Germany) Karsch. The family immigrated to the United States, arriving in New York on January 29, 1864, and settled in Tennessee.

Fred was heavily involved in Republican politics, not a popular part in the postwar South. He was part owner of Karsch Brothers, a popular German bar on Cedar Street in Nashville. He was charged with tippling on Sunday April 7, 1867 for selling beer. The law was intended for liquor and spirits, and he won the case, but it took years and appeals courts to determine the outcome.

During May 1871, Fred married Louisa M. Buddeke and later had two children.

On February 23, 1872, a gun was pulled on him by a patron because he did not deliver drinks fast enough.

While his saloon was praised for having fine Cincinnati beer and choice wines and liquors, in 1876, the firm went bankrupt. Also in 1876, October 16th, Fred and Louisa’s daughter died.

Fred moved to Cincinnati, apparently leaving his wife and son behind until he could afford to bring them north. Initially, he kept a bar at 269 Vine Street.

During April 1880, Republican Mayor Charles Jacob, Jr. appointed dozens of officers to the Police Force, including Karsch to the 9th Ward. He also appointed Patrick Rainey to the 8th Ward. About mid-October 1880, Patrolmen Karsch and Rainey were appointed as partners in Bucktown, the general area north, east, and south of 6th and Broadway.

Bucktown was deemed by The Cincinnati Daily Enquirer to be the most dangerous place in the country. Officer Nuttles was killed there in 1862. Officer John Holland was almost killed there during 1875. Officer James Whalen was stabbed in the abdomen in Bucktown about March 1879 by David Wakefield and he almost died. During November 1880 it was still assumed that his wounds would eventually kill him. Officer Moffet’s throat was cut in Bucktown about June 1880 by murderer Jim Grant, but Officer Moffet survived.

MURDERER

Charles Marshall was born in 1853 in pre-Civil War Kentucky according to his burial card. We believe he came to Cincinnati in early 1875 because he suddenly started showing up on police blotters. Initially, he settled in Bucktown.

On July 27, 1875 he was bound over to the Grand Jury on a charge of Grand Larceny. Later in the year, September 17, 1875, after John “Red” Williams identified persons involved in a theft and Marshall accused him of “giving away” his associates and stabbed him with a knife. Only Williams’s defensive movement prevented the knife from going into his heart.

Marshall was a barkeeper for an establishment at Culvert Street and Cork Alley in Bucktown in the beginning of 1876. Between 1 a.m. and 2 a.m. on February 6, 1876 he was drinking and playing cards at Butler’s at 204 Broadway between 5th and 6th Streets when an argument broke between him and Red Williams. One accused the other of cheating and Williams pulled out an empty revolver and snapped it at Marshall to scare him. Instead, Marshall pulled out a large knife, charged Williams, stabbing him twice. This time, he did get Williams’ heart and Williams fell dead. He was charged with Murder. He went to court on February 7, 1876 and the case was continued. He was bound over to the Grand Jury on a Manslaughter charge on February 9th.

A month later, on April 16, 1876, Marshall participated in another affray when he cut George Swan in the head with a hatchet, before George Davis shot Swan in the chest at Davis’s house. Swan survived and both men were bound over to the Grand Jury. Marshall was indicted for Cutting.

Marshall, by then working as a steam boatman, was arrested on a charge of counterfeiting on November 13, 1877.

We have found no indication that Marshall ever answered for any of his crimes.

INCIDENT

On November 3, 1880, Patrolmen Karsch and Rainey came on duty at 7 p.m. At 10 p.m. they were attracted to a crowd of people on the sidewalk east of Broadway on East Sixth Street. They were being loud and disorderly, still celebrating the election of Republican James Garfield on the previous day. Patrolmen Karsch and Rainey were both Republicans and also happy with the election, but their duty was to disperse the crowd. Patrolman Rainey followed two disorderly men as they left the area west on Sixth Street.

As Patrolman Rainey was returning, he heard 27-year-old Charles Marshall yell, “No G—damned police can make me disperse! I’ll shoot the first G—damned son of a bitch that touches me.” Rainey ran to help.

Patrolman Karsch followed Marshall toward the curb and Marshall drew a British Bulldog .42 caliber revolver and turned. Patrolman Karsch grabbed Marshall and Patrolman Rainey grabbed the pistol. Marshall began firing. The pistol had a short barrel and Patrolman Rainey had little leverage to hold it. While he held it with his left hand, he was striking at Marshall with a billy club in his right hand. Of the first three shots, the first went wild and the next two went into Patrolman Karsch’s leg and abdomen. Marshall yelled again, “G—damned police! Son of a bitch!” Patrolman Karsch said to Rainey, “Partner, don’t let him go. I’m gone.” Finally, a blow from Rainey’s club knocked the revolver from Marshall’s hand.

Patrolman Lawrence Crambert, upon seeing and hearing the struggle and shot, came to assist, and arrived within a minute. Rainey told him that Marshall had killed his partner. Crambert went to Patrolman Karsch, who was still standing, and asked if he was hurt. He replied, “Yes, I’m killed.”

Patrolman Karsch collapsed, and the officers carried him to Hellman’s drug store on the northeast corner of Sixth Street and Broadway. Dr. Jacob Trush, of 140 Broadway, responded from his home to treat him. By then, Patrolman Karsch was unconscious. The doctor administered brandy, but with no effect.

Lieutenant Thomas ordered a teletype sent to the City Hospital for an ambulance. Bucktown was such a dangerous neighborhood that no one wanted to enter the area. Forty minutes later, when no ambulance had arrived, he sent for a hack which was almost equally as slow in coming. Patrolman Karsch was eventually transported to Cincinnati Hospital.

DEATH

Patrolman Karsch died at the hospital at 5 p.m. the next day, November 4, 1880, from the pistol-ball passing through the right side, through the liver, and causing internal hemorrhaging.

He was predeceased by his daughter, Mary Anna Ellen “Mame” Karsh. Patrolman Karsch was survived by his wife, Louisa M. (Buddeke) Karsch, and son, Joseph H. Karsch (4). At the time of his death, Louisa was still in Nashville and Officer Crenshaw telegraphed her to inform her of his death. By nightfall on the 4th, no response had been received from Tennessee, so Inspector Meyer took possession of the body and put it on ice at the City Buildings in the Central Station Armory.

A funeral was held at 2 p.m. on November 7, 1880. For an hour, his body lay in state in City Council chambers as 5000 people of all colors and conditions viewed the body. Over the casket was a silver plate inscribed, “Frederick Karsch – Died November 4, 1880 – Aged 36 years, 3 months, 5 days.” A funeral service was held there, presided over by Reverend Kamerer. The funeral cortege left the City Buildings and went up Vine Street. He was escorted by two companies of police and the police band. Pallbearers included Captain Meyer, Inspectors of Police, Lieutenants Borck and Thomas, Sergeants Thornton and Robinson, and Patrolmen Webb and Rainey. The hearse carriages contained the Mayor, Chief of Police, and their clerks.

Patrolman Karsch was buried without a grave marker in Section 9, Grave 418 of the Vine Street Hill Cemetery on the Carthage Pike near St. Bernard.

INVESTIGATION

While in the hospital, Marshall was questioned by Officer Lawlor and admitted firing the revolver, though he said that he did not know who he was shooting.

Doctor Walker, of the hospital, completed the postmortem examination.

Coroner Carrick held an inquest on November 5, 1880 and it continued to the morning of the 6th.

JUSTICE

Marshall’s case was on the Police Court docket on November 4th, but he was in the City Hospital and the case was continued until November 11, 1880. Marshall was released from Cincinnati Hospital later on the 4th and taken to the County Jail.

On the 11th, his case was continued another week.

The Hamilton County Prosecutor on November 23, 1880 announced that a Grand Jury had ignored the case deciding there was insufficient evidence upon which to find a true bill against him. Marshall was released – again.

EPILOGUE

On December 11, 1880, Marshall responded to the office of the Police Chief demanding the return of his revolver. We suspect he was less than civil in his demand. As he left the stationhouse, he concealed the firearm and was promptly arrested for carrying a concealed firearm. The disposition of the case is not known.

There is a vague report of Marshall killing another man in 1881, but we cannot confirm it.

On November 14, 1881, Marshall was arrested again on suspicion of possessing stolen merchandise, a fine silver cake dish. A couple of weeks later, on November 29th, he stole a man’s shoes while he slept. The man awoke and Marshall gave him a severe beating. He was again arrested, charged with petty theft and assault and battery.

Marshall was in a bar on Rat Row on Front Street on February 18, 1882 and got into another argument. This time the other man had a pistol and started shooting. Marshall, uninjured, ran for his life. The bullet struck an innocent person, Mrs. Moore.

During the primaries for the 1883 election, Marshall, by now married and living at #8 Gano Alley, wanted his name on the Republican ticket in the 6th Ward. His name was not listed, and he blamed his would-be opponent, Albert Anderson. On the date of the primaries, August 15, 1883, Marshall caused a ruckus and again pulled a revolver. Before he could use it, Anderson lunged and stabbed him with a pocketknife. Marshall died on the way to the hospital. He was buried in United Colored Cemetery in Madisonville.

Louisa and Joseph Karsch never did come north. Louisa died 27 years after her husband and is buried in Nashville. Joseph became a medical doctor, married, had two children, and died in Baltimore and was buried in Nashville. Frederick Karsch had only one great-grandchild, U.S. Representative Donnelly J. Hill, who died without issue in 1976.

On December 2, 2014, Joyce Meyer, Price Hill Historical Society Researcher notified the Greater Cincinnati Police Museum Director that she had found in her research another Cincinnati officer, Patrolman Schnucks, had died in the line of duty. The Museum conducted extensive research and confirmed that the officer had indeed died in the line of duty. Then, after several months, the Historian, Cincinnati Homicide Detective Edward W. Zieverink III (Retired), found where Patrolman Schnucks was buried and that he had no headstone. While conducting his research, he also found that Patrolman Karsch was buried without a grave marker about one hundred feet from Patrolman Schnucks.

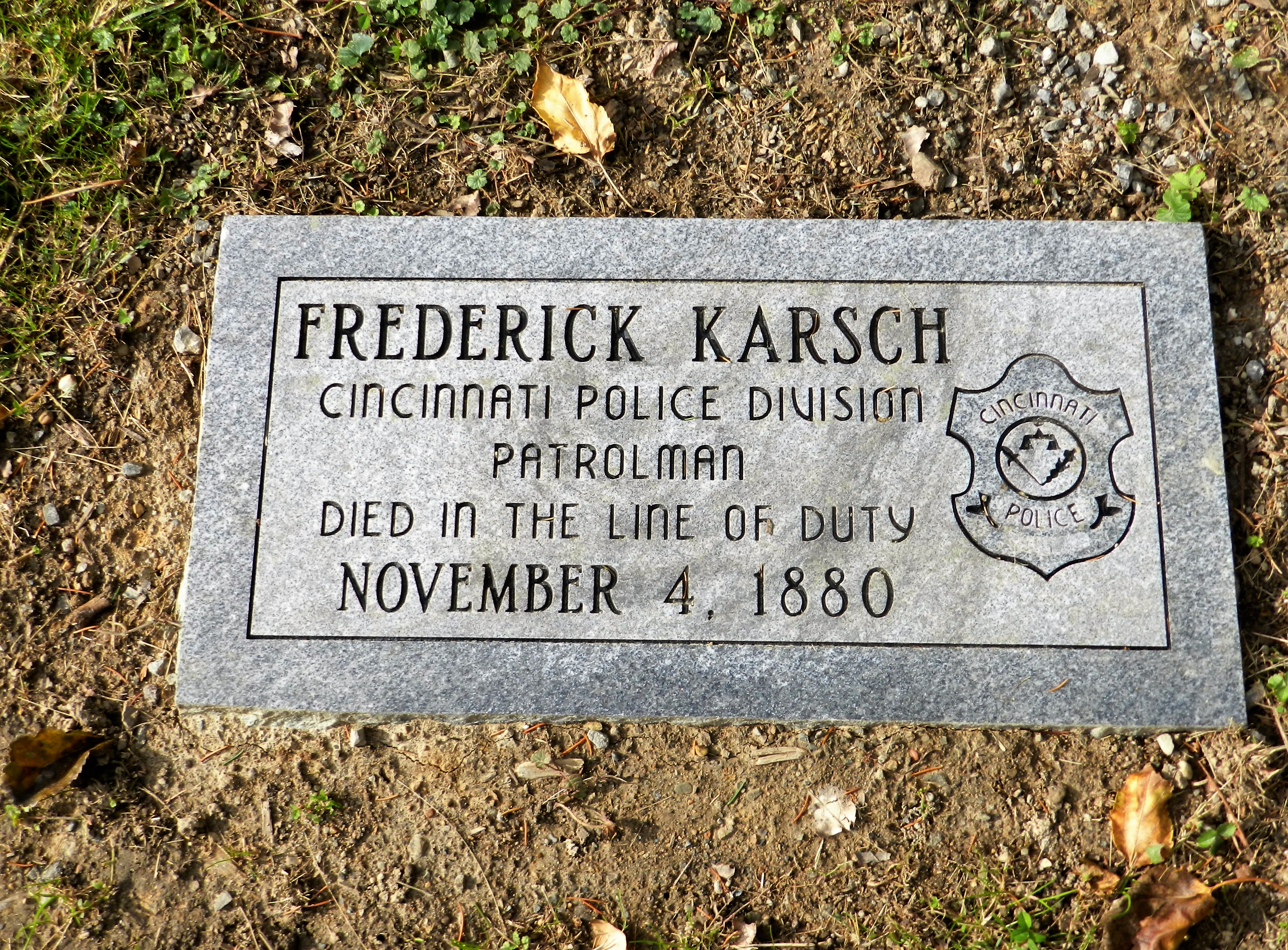

The Museum worked with the Vine Street Hill Cemetery, Cincinnati Police Department, Hamilton County Police Association Honor Guard, and Schott Monument to honor both officers by rededicating their graves with the pomp and circumstance due them, and to mark their graves with headstones on November 3, 2015.

Additionally, Vine Street Hill Cemetery who had already erected a memorial to fallen police and fire officers, refurbished that memorial and it too was rededicated by the Hamilton County Police Association Honor Guard.

If you know of any information, archives, artifacts, or images regarding this officer or incident, please contact the Greater Cincinnati Police Museum at Memorial@Police-Museum.org.

© This narrative was further researched and revised on October 28, 2021 by Cincinnati Police Lieutenant Stephen R. Kramer (Retired), Greater Cincinnati Police Historical Society President, with research assistance and information from Joyce Meyer, Price Hill Historical Society Researcher, and Cincinnati Homicide Detective Edward W. Zieverink III (Retired), Greater Cincinnati Police Museum Curator. All rights are reserved to them and the Greater Cincinnati Police Historical Society.